October 9, 2013, was the day of the Presidential elections in Azerbaijan. As predicted, the incumbent, Ilham Aliyev, was re-elected to a third term as President, a position that was inherited from his father, Heydar Aliyev, a former Soviet KGB officer, and President of Azerbaijan during most of the 1990's and the early 2000's.

Quite by chance I met some of the international long-term election observers in Mingachevir several weeks ago. Since they were in need of translators, they asked for my help in recruiting additional translators, who could serve before, during, and after the elections as interpreters for the short-term international observers and for the international journalists expected in country to cover the elections. I have a number of very accomplished and dedicated professionals in Mingachevir, who over the past several years have regularly attended my advanced English classes, so it was a pleasure and an honor to recommend them. After the interview process, some of them were chosen to work this past week as translators/interpreters. I was pleased and proud to be able to offer them an opportunity to have a chance to utilize their greatly improved English skills, albeit for only a short time, since they show such eagerness and willingness to work hard and improve their skills.

Today, one of the international long-term election observers called me to thank me for the efforts I went to in order to help them find appropriate translators. Then she told me that every single one of the young women I suggested and whom they interviewed for the positions had such glowing things to say about my efforts as a Peace Corps Volunteer--things like my help and my involvement in teaching them has for them been transformative and life-altering!! Wow, I'm thinking...I am humbled--I did my part, to be sure, but never have I come across a group of young women, who willingly work so hard and go to such great efforts on their own initiative in order to make improvements in their lives. Today this group of women told me again that they will miss me and they appreciate my efforts. But the best thing they told me is that they intend to continue meeting after I leave Peace Corps Azerbaijan--even without me, they intend to learn, support, train, and help each other. Wow!!! Most of their accomplishment has not been due to me, but to their own desire and their industriousness. And this effort towards sustainability of my work is truly satisfying.

They say Peace Corps is the "toughest job you'll ever love"--tough because it is definitely full of many living and work challenges. But Peace Corps service is also one of the most rewarding and satisfying of endeavors. Today turned out to be one of those very satisfying days!

Friday, October 11, 2013

Thursday, September 26, 2013

Transportation in Azerbaijan...or how to spend a weekend pretending you are Indiana Jones

Transportation in Azerbaijan :

Azerbaijan is a small country, but roads and other

infrastructure issues make transportation from one site to another quite

challenging, and even from one part of town or region to another. Of my local friends and associates, I can

think of no one who owns his own car, so reliance on public transportation is

the way to go. In the town where I live,

Mingachevir, walking everywhere or taking a local in-town bus is what we do. A ride costs about $0.25. There are also taxis, basically operated by someone who

has pooled the family’s financial resources and bought a car, often a well-used Russian Lada, on the top of which is loosely placed a plastic "taxi" sign. They line up on virtually

every corner, waiting for someone who needs the $2-$5 ride from one part of

town to the other, or to the beach of the Mingachevir Reservoir. You always negotiate the price before getting

into the taxi!

|

| At the bus stop in center of town taxis wait to pick up a fare |

|

| The red and blue car are taxis, hoping to get a fare off of the marshrutka (white van) |

|

| Blue marshrutka takes passengers all over town for $0.25 |

|

| Taxis wait on every street corner to pick up a fare. Rule of thumb: women never sit in front next to the driver! |

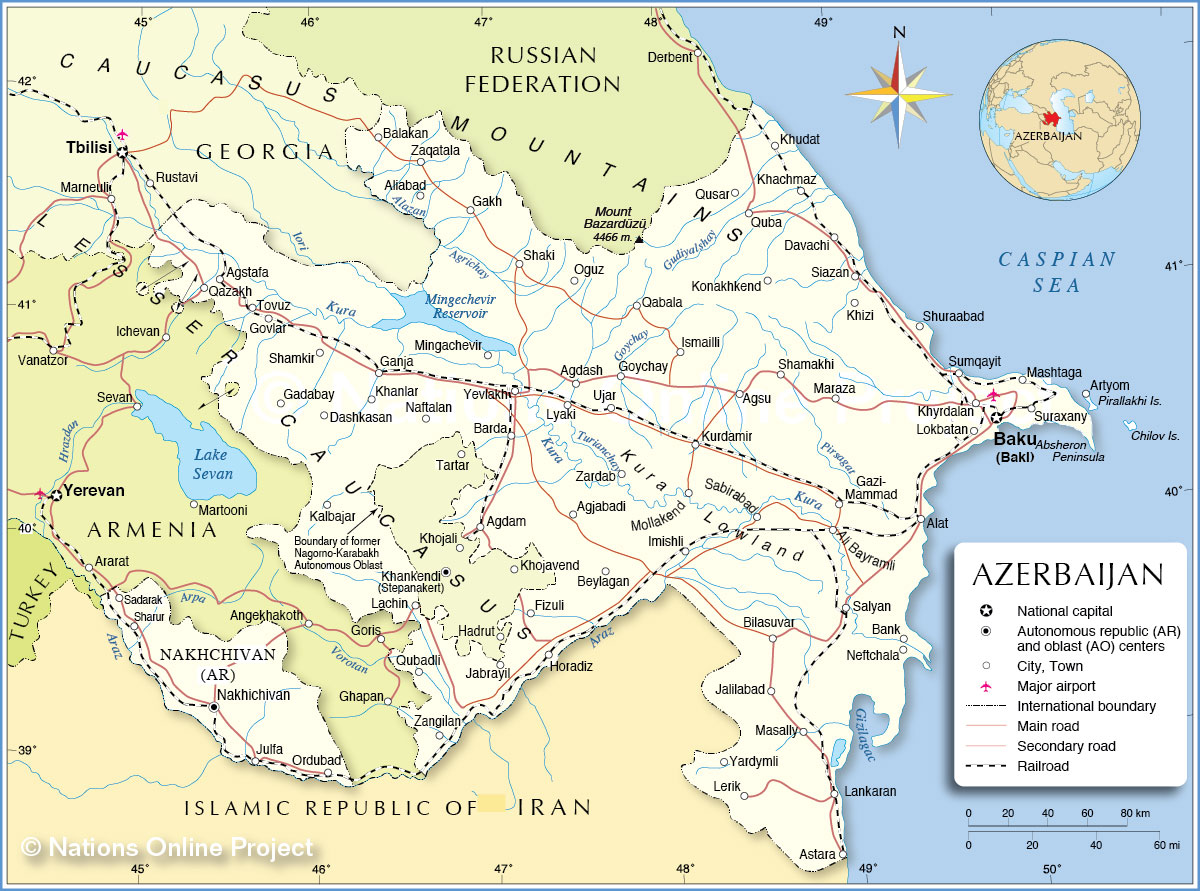

Looking at a map of Azerbaijan ,

we say that the country looks a bit like the palm and fingers of your right hand, with Baku being located on the thumb sticking out into the Caspian Sea, Quba and

Qusar on the first finger, Sheki, Qax, Zagatala, and Balakan on the second

finger, Tovuz and Gence on the third, and everything else is in the palm of the

hand or “down south.”

To get from one major region to another (we say from one finger to another), one must travel first to Baku and then transfer to go elsewhere—by

bus! Only recently have there been some

regional airports that have opened sporadic service to Baku , and I know of no one who uses such

service—it would be cost-prohibitive for most Azeris, and Peace Corps

Volunteers, for sure! From larger towns,

there may be bus service using a large, fairly comfortable and air-conditioned

bus; these buses leave on a fairly regular, but rather infrequent, schedule, to Baku . Most people, however, just show up at the

local avtovagzal (bus station) and climb aboard a marshrutka (mini-bus) to

where-ever they want to go. The

marshrutkas depart once they are full. The

marshrutka ride to Baku takes about 4 ½ to 5 hours, including a tea break at a

local rest stop, and the driver only sells enough tickets for the number of

seats. Marshrutkas are often cramped and

very well-used, with narrow, sometimes torn, seats. If necessary, between towns and villages

where the ride may only take an hour or two, people are packed in like

sardines, sitting on wooden stools in the narrow aisle, or standing in crowded

fashion, leaning for the sake of stability over those lucky enough to be seated. Sharing the ride with some live chickens that

a farmer’s wife wants to bring to market is not uncommon. And these marshrutkas on local runs between

neighboring towns stop to pick up passengers on the side of the road going in

the same general direction; they simply flag down the marshrutka, and it always

seems possible to squeeze yet one more onto the little bus.

|

| Marshrutkas stop at a rest-stop to allow passengers enjoy a tea break. Many have hawkers selling snacks, little toys and CD's for the continuing ride and use the restroom  |

Riding the marshrutkas around the country has been part of

the adventure of living here. My little

granddaughter, Kaitlyn, loves the Indiana Jones ride at Disneyland ,

and I have told her that the marshrutka rides here are a little bit like

several hours-long Indy rides. Some

marshrutkas have worn-out springs and shock-absorbers, and since the country is

trying to modernize its roads, there is construction on many roads, with many

stretches still full of pot-holes. Other

roads get washed out on occasion and are simply roads of dirt and rocks. But this is not the only adventure. Sometimes fellow passengers or the bus driver

want to entertain you with traditional Azeri music, and to make sure you get

the full force, blast it very loudly, just like at a wedding, where

traditionally the Azeri music is played so loudly, no one can carry on a

conversation. Other adventures include

having a driver who loves to play “chicken” with on-coming traffic; the first

time I witnessed this, and then the swerving sharply to avoid a head-on crash onto the rock-strewn shoulder, I

was scared to death—now it just seems part of the “adventure ride.” Drivers also smoke, talk on cell-phones, and

sometimes argue and gesture with passengers.

No one wears a seat-belt—they don’t exist. The rides are so bumpy, hot, and crowded that

often passengers must carry plastic bags into which they can relieve themselves

of their car-sickness. I have not had

that problem personally, but sitting next to one who is violently car-sick…well,

not so pleasant. And then, according to popular opinion, you can get ill from sitting in a draft, so even when the weather is 110 degrees Fahrenheit outside, most passengers would rather ride inside an oven than crack a window for some refreshing breeze.

|

| Views inside the marshrutkas |

|

| Seats can be attractively covered--and it hides rips and tears, too. |

One adventure occurred on a ride from

Some people live a great enough distance from

Traditional modes of transportation are also frequently

noticed and a charming part of life in the regions of Azerbaijan.

Some modes of transportation also serve as a sort of market--a place to buy what you need...

What will I miss about travel in Azerbaijan ?—Well, you may get a

more comfortable and certainly a much more spacious seat on the likes of Southwest

Airlines, but the idyllic view of flocks of sheep crossing the road and causing

traffic to come to a stop or a carefully maneuvered slow-down are some of the

memories that will always make me smile.

Thursday, September 12, 2013

Peace Corps Azerbaijan: 10 Years of Service

What is Peace Corps service in Azerbaijan like?? Check out this video created by my fellow PCV Stephan Jackson, AZ9, for a glimpse into some of the activities and things of service we do here!

Thursday, June 20, 2013

German-Azerbaijanis.......and German-Americans.......

German-Azerbaijanis.......and German-Americans

Being ethnically

German-American, I have an innate interest in the fact there are some definite

parallels to the stories of the German settlements in Azerbaijan and the German settlements in America Ukraine

and the Caucasus .en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caucasus_Germans

In both cases,

German immigrants faced many hardships, but banded together in their new

settlements to retain their cultural and religious heritage, both in America Germany

(Interestingly,

political unrest in the Russian empire half a century later, during the latter

years of the nineteenth and early years of the twentieth centuries, caused

additional hardships for those German immigrants now living and farming in Russian

territories. So, many of those Russian-Germans, especially those from

regions of the Ukraine , with

its large wheat and grain fields, packed up and emigrated again, this time to

the vast stretches of open spaces in the U.S.

and Canada Odessa , Washington , a

small wheat-farming community in Eastern Washington, my home state, was in fact

named after the major city in the Ukraine --Odessa , as a way to entice these new Russian-German

settlers to the wheat fields which to this day prosper in Eastern

Washington . This Washington

State community has also not forgotten

its heritage, and yearly in the fall a Deutschesfest is held in Odessa , Washington to

celebrate and commemorate its German roots, albeit via Russia and the Ukraine

The two World

Wars of the twentieth century also impacted, often quite negatively, the German

settlements and the German immigrants in America

and in Azerbaijan Germany America

But the fate of

the German-Azerbaijani communities was much harsher, during the years leading

up to World War II, as the Soviet Union leader Joseph Stalin rounded up all who

were living in the German settlements and those with German-sounding names, and

had them deported to Siberia and Central Asia, i.e. Kazakhstan. As the

fear of Nazi encroachment and battles in Russia raged, it became imperative to

Stalin to rid the all-important land with copious oil and gas

reserves--Azerbaijan--of its ethnic German citizens, who might in Stalin's view

offer aid to the Nazis (who definitely had their eye on Azerbaijan's oil and

gas for Nazi war effort), despite the fact that the German-Azerbaijanis had

lived more than a century as citizens of the Russian empire and subsequently

the Soviet Union. This fear and paranoia is not unlike what happened to

"Japanese-Americans during World War II, who were first held in great

suspicion by the American public and then deported almost entirely to

internment camps, as the American public feared they were not completely loyal

to the United States

During the

round-up and deportation of German-Azerbaijanis, some German-Azerbaijanis left

their children behind to be raised by ethnic Azeri neighbors. And some,

like a friend I have made at the German

Lutheran Church

in Baku , have been allowed to return to Azerbaijan Kazakhstan

Today, several of

these former German communities in Azerbaijan are undergoing a revitalization

program, intended to renovate the buildings and streets, homes and Lutheran

churches of these German-Azerbaijanis of long-ago. One such community

today is known as Goygol, but to the Germans of its day it was called

Helenendorf; and today's Shamkir was once known to its German settlers as

Annenfeld. The vineyards, surrounding these settlements, which the

Germans planted and tended (they were all originally from Wuerttemberg) are

still there today, as are the remnants of wineries with such names as

Concordia.

Several weeks

ago, a group of members from the Baku German

Lutheran Church and I traveled to these communities to meet up with a

delegation from Bonn , Germany ,

which supports the church in Baku Bonn , they were interested in

the history of the German settlements in Azerbaijan ,

and the Azerbaijanis (most of German descent) were likewise interested in

learning more about their heritage together with these friends of their congregation

from Germany Kazakhstan

|

| |

|

|

| Interior is being renovated in order to create a cultural center and German heritage museum |

|

| District cultural director explains the renovations

to visitors from |

| |

|

|

| Park in Shamkir (Annenfeld) |

|

| The Minister of Taxes, the government official

responsible for this region, entertains us with a feast for lunch--3 kinds of kabab, salad, soups, tea and sweets--and of copious amounts of bread. |

|

| Facades of houses are being renovated to remind visitors and residents of the town's German heritage |

|

| On the road between Shamkir (Annenfeld) and Goygol (Helenendorf) |

|

| Pastoral alpine views between Shamkir and Goygol |

|

| And we were treated to tea and cakes in an old wine-cellar, turned restaurant, and offered wine-tasting |

|

| German-style street scene in Goygol (Helenendorf) |

|

| Off in the distance, Narorno-Karabagh--bitterly disputed lands, technically Azerbaijani territory, but occupied by Azeri arch-enemy, neighboring Armenia |

|

| Inside the Goygol home of Victor Klein, last surviving descendant of German settlers |

German Lutheran Church in Goygol,

housing a German-heritage museum

|

| Helenendorf's Town Hall (Rathaus) |

Following WWII, German prisoners-of-war on Soviet soil were detained and used as laborers to rebuild parts of the Soviet Union, including Azerbaijan. Towns, including Mingachevir, where I live, were built by German prisoners-of-war, as well as the dam and power plant on the Kur River, Mingachevir. These cemetery views in Goygol show the graves of German prisoners-of-war, those who died here, still in captivity long after the end of the war, as well as the graves of the German settlers of Helenendorf.

"Here rest the prisoners of war--victims of the Second World War...may God have mercy on them and all victims of war"

The German prisoner-of-war graves join the graves of the German Christian settlers who for more than a century lived and worked throughout this region.

In years past, after the German settlers had been deported to Central Asia and Siberia, the German cemetery was vandalized by local Azeris, thinking that the Christian graves were perhaps Orthodox Armenian (their arch-enemies), not realizing nor being able to discern that they were the graves of German Lutherans

Nagarno-Karabagh is off in the distance...the region occupied by Armenia, but technically part of Azerbaijan

The overnight Night Train to and from Baku was in and of itself an *experience*

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)